Sun 2026-02-01

Trigger warnings: depression; PTSD; suicidal ideation; barriers to care.

Seeking Counselling in the UK: What worked, what didn’t, and what I wish services understood

Recently, I found myself seeking mental health support for the first time in my life. I’ve written about the incident in detail HERE. Here is a short summary:

A streamer I considered an online friend, who we’ll call Esmeralda, suddenly became hostile towards me and accused me of wrongdoing I didn’t understand. Soon afterwards I was banned from several online communities I’d belonged to for years, and people said terrible things about me publicly, while I was unable to respond. Nobody asked me what happened either at the time or subsequently. I felt my voice had been erased. The shame, isolation, and confusion triggered a severe depressive episode and PTSD-like symptoms.

Later, I learned I might be autistic, which reframed how the misunderstanding could have happened and why it hit me so hard. I've written about that journey HERE. This article is about what I did next: trying to access mental health support in the UK, what worked, what didn’t, and what I wish services understood about trauma and neurodivergence.

Table of Contents

- Seeking Counselling in the UK: What worked, what didn’t, and what I wish services understood

- Background: The Impact of The Incident

- Seeking Support from my GP

- The NHS Talking Therapies Process

- The Rejection and Its Impact

- Turning to Private Counselling

- Beginning Counselling and Early Experiences

- A Specialist or Generalist?

- Reflections and Future Hopes

- Conclusion

Background: The Impact of The Incident

After the incident I became severely depressed. I lost my appetite, had nightmares, struggled to get out of bed, and felt crushing guilt and shame. In a private document, I wrote at the time: “How do I rejoin the human race after committing such unforgivable evil?”, which seems melodramatic now, but is reflective of my mental state back then. I was in a dark place.

Over time, the depression became less constant, but I was left with PTSD-like symptoms:

-

Anxiety and depression triggers: words like “creep” and “stalker”, certain place names, and even objects like chocolates and bath salts—reminders of the shared history between Esmeralda and me.

-

Aversions: I now avoid anything triggering; for instance, I haven’t enjoyed a long, relaxing bath since the incident (see bath salts above).

-

Nightmares: I often dream of being tormented by members of the streamer network Esmeralda is a part of, or wake up with the memories of phrases like “she's not comfortable with you anymore” or “I never want to meet them” in my head.

-

Anhedonia: Activities I once loved no longer bring me joy.

-

Intrusive thoughts: The incident occupies my mind daily, even though I wish it wouldn’t.

-

Social anxiety: My social anxiety is worse than ever.

-

Anxiety around romance: I find the idea of deliberately romancing a woman repulsive now. Whenever I hear stories of people making romantic gestures, be it fictional or real, I cringe.

-

Ongoing bouts of depression: I continue to struggle with it from time to time.

Eventually, I realised I wasn’t recovering on my own, and I needed help from my GP.

Seeking Support from my GP

At the point when my emotional state hit its lowest, I didn’t seek help. I suppose it had something to do with both blaming myself, and because it seemed to me a natural reaction to something upsetting, not an underlying depressive mindset. This made me think that a doctor wouldn’t be able to do much for me other than prescribe medication that would change my brain chemistry (with all the side effects you’d expect). Furthermore, when I shared my struggles with friends and family and my mood began to pick up a little, I mistakenly thought I would just keep feeling better, and so I didn’t look for help then either. But eventually, my mood settled into a new stable low, but higher than before, with PTSD-like symptoms continuing, which made me realise that I needed to talk to my GP (doctor).

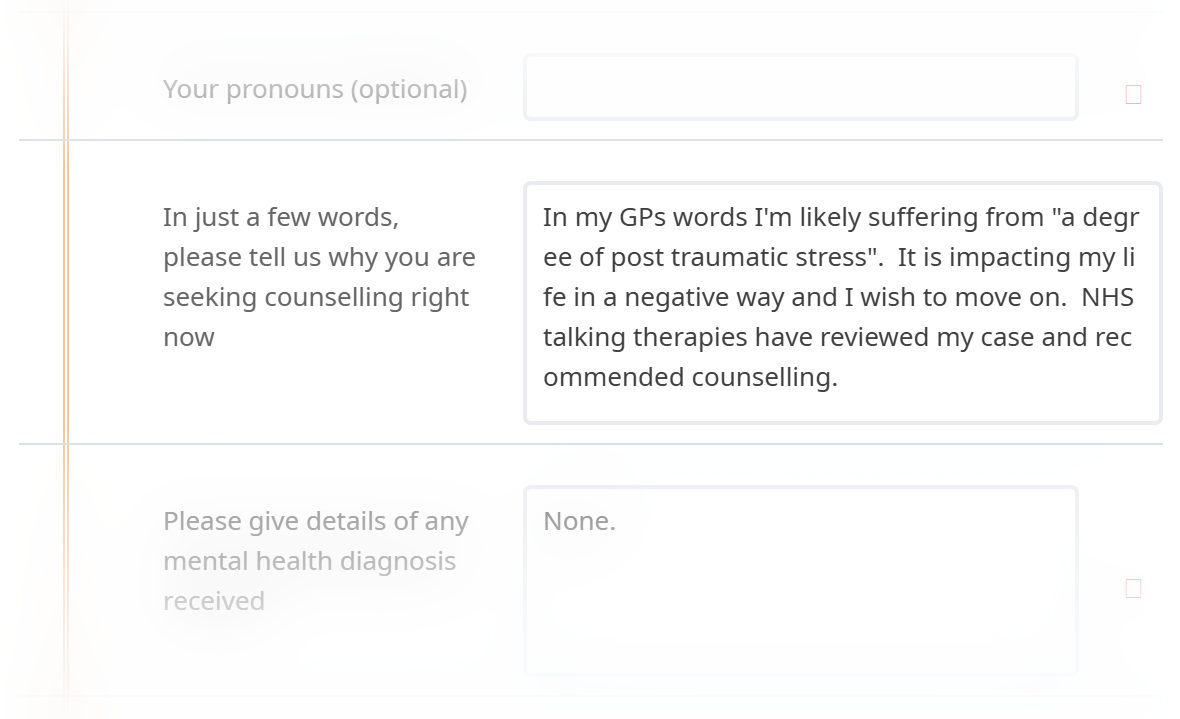

I called to book an appointment, and this being the NHS the first available slot wasn’t until a few weeks later. On the day, as I walked to the GP surgery, I rehearsed what I would say. Preparing ahead helps ease my anxiety, even though I can’t predict how others will respond. I carefully weighed how much detail to share—enough to explain my symptoms without overwhelming her. I deliberately avoided terms like PTSD or trauma, as I didn’t want to bias the diagnosis. My doctor was already aware that I might be autistic.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from my appointment, but my best guess was I’d be recommended either cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), or anti-depressants, or both, and I wasn’t far off. My doctor recommended I self-refer for CBT, for which she sent me an e-mail with a link. She mentioned that had I come earlier, when the suicidal ideation was worse, she would probably have prescribed me anti-depressants. She has said that I was probably suffering from a degree of post-traumatic stress.

My doctor’s recommendation to self-refer for CBT marked the beginning of navigating the intricate process of getting support from NHS Talking Therapies.

The NHS Talking Therapies Process

The umbrella service is called NHS Talking Therapies (NHS-TT), you can learn more here. To get started, I used their website to find the closest local service, which took me to another website. From there, I filled in some online forms. First, I answered a series of yes/no questions like whether I was over 17, if I lived in the right area, if I understood they couldn't help in emergencies, if I knew I couldn't use their service if I was planning to take my own life, and if I agreed to their strict appointment rules (if you miss an appointment, you could be discharged).

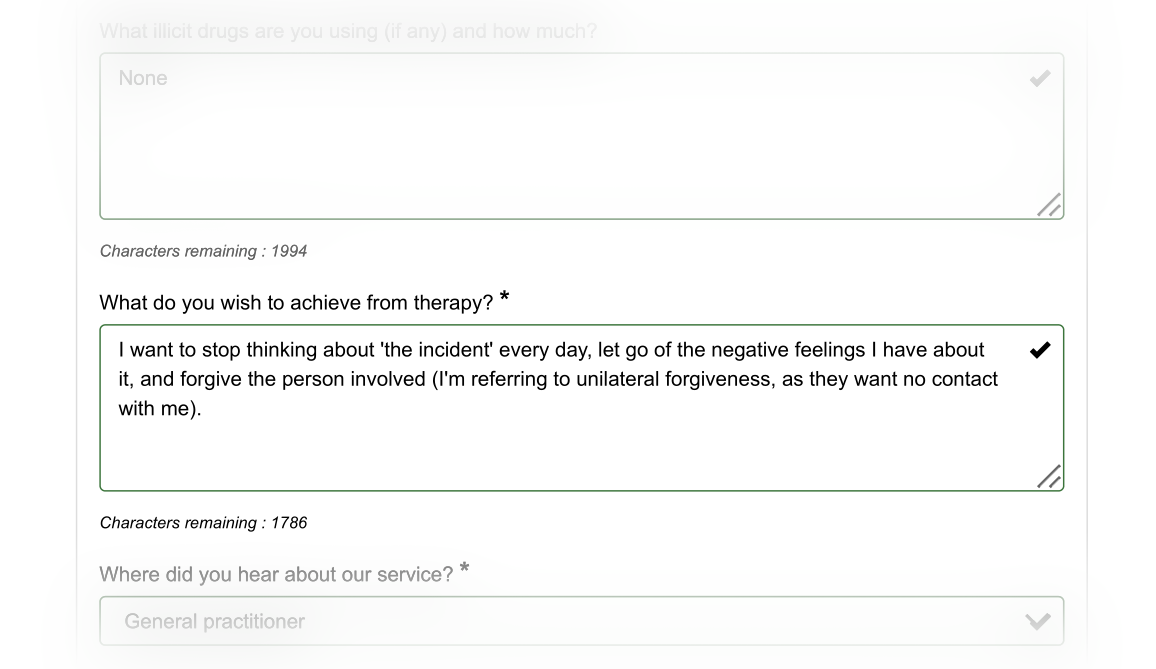

After that, I moved on to the self-referral forms and various questionnaires about my mental health. The self-referral form was detailed. It asked for my contact information, a brief description of my current problems, whether I was feeling suicidal, if I was a carer, and how much alcohol I consumed weekly. I also mentioned that I was due for an autism assessment in a few weeks.

When asked about my goals for therapy, I wrote: “I want to stop thinking about 'the incident' every day, let go of the negative feelings I have about it, and forgive the person involved (I'm referring to unilateral forgiveness, as they want no contact with me).” Here I was referring to my forgiving Esmeralda; I doubt that she will ever forgive me.

It may come as a surprise to some readers that I felt there was anything to forgive, but after all the pain and suffering I've faced and still face, along with the feeling of being betrayed by someone I trusted, and having doubts about whether Esmeralda had been completely honest with me, I do feel wronged. Furthermore, I'm really struggling to find a way to forgive someone who:

-

is actively hostile to me;

-

seemingly feels no remorse; and

-

would probably do it again if they had the opportunity.

The questionnaires included a lot of yes/no questions to assess my levels of depression and anxiety among other things over the past two weeks. At that time, I was feeling quite hopeful, so I indicated that my levels of depression and anxiety were fairly low.

It's important to note that once I submitted these forms, I couldn't access them again, so if you want to keep a copy, make sure to do so before moving to the next page. I later e-mailed NHS-TT to ask for a copy of the questionnaires, but all I received back was the self-referral form and a record of some messages. Some of these messages were internal ones that I hadn't seen before.

After completing the self-referral process, I received an e-mail with a link to book an over-the-phone assessment. I secured an appointment just five days later—a pleasantly swift turnaround for an NHS service. The day before my appointment, I was asked to fill in several questionnaires again; I’m not sure why I had to do them twice—maybe to see if anything had changed?

During the phone appointment, which was with a Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP), I was asked many of the same questions again, including what my treatment goals were, which I repeated. She reworded them as “I would like to get to point where I can forgive the individual and process what has happened”. She seemed very eager to use the word “processing”. I understand what “processing” means in general, but I’m not sure what it really means in a situation like this. If I asked you to “jump now”, you’d know what I meant even if you thought I was being rude, but if I asked you to “process grief”, what would you do, concretely? I also don’t think my original goals were unclear.

This time I had more opportunity to share details about the incident. I poured my heart out and shared everything with the Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner. She listened and said that I had clearly been through a lot. She mentioned she would send me another questionnaire about PTSD and would discuss my case with her supervisor to arrange for help, but cautioned me that the team dealing with PTSD cases was small.

She seemed to genuinely care, and it made me feel even more hopeful—until the following day, when I received news that shattered that hope.

The Rejection and Its Impact

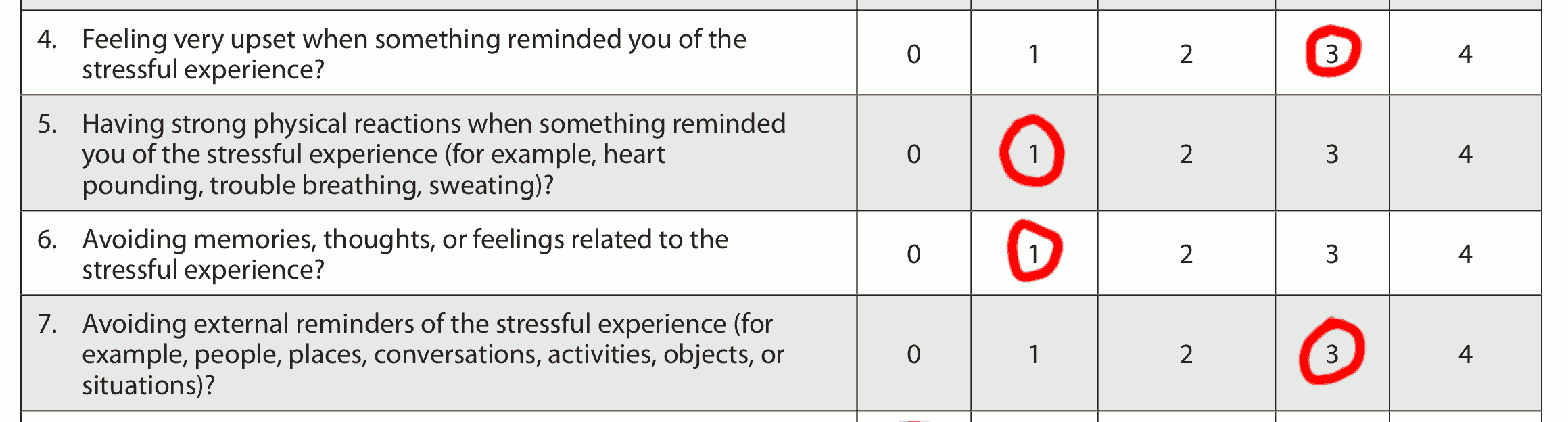

I got the PCL-5 form through e-mail, filled it in, and sent it back. The next day, I was informed that after discussing my answers with her supervisor, they thought I should get some counselling instead and would be referring me back to my GP (doctor). I felt devastated. I also learned the results of a few of the questionnaires I had completed.

My PHQ-9 score came in at 9 out of 27—suggesting mild depressive symptoms. The GAD-7 score was 4 out of 21, pointing to minimal anxiety, and my PCL-5 score was 28 out of 80, which they called non-clinical PTSD.

They didn’t explain why they decided not to take me on, so at the time I was left guessing. Following an information request, I learned that my PCL-5 score did not meet the cut-off they have chosen for their PTSD pathway. NHS Talking Therapies don’t publish this cut-off, and the PCL-5 doesn’t have one single universally agreed threshold, but some research online suggested that my score wasn't far below thresholds that are commonly used for the PCL-5 by other services.

I understand why services use questionnaires: they need a consistent way to triage and to match people to the treatments they can offer. The problem isn’t that questionnaires exist; it’s when they become the whole decision, rather than one piece of evidence alongside clinical judgement and real-world impact, especially when:

-

the questionnaire is self-report

-

over a short time window

-

where symptoms fluctuate, and

-

functional impairment isn’t captured well.

When I filled in the forms, I was in a brief upswing because I thought I was finally going to get help. I answered honestly for that fortnight — but in retrospect the timing meant the scores didn’t reflect my baseline, or how badly I can be affected when my symptoms get worse.

Funnily enough, this rejection triggered another bout of depression. As I mentioned earlier, my depression had been coming back at irregular intervals by this time (and it still does). I confided in a friend that:

“Maybe counselling would be a better fit for me, but having to go through so much just to be turned away makes me feel like my mental health doesn’t matter.”

I felt undervalued and dismissed. I knew I had to explore other avenues for support. This led me to consider private counselling as my next option.

Turning to Private Counselling

NHS-TT was nice enough to give me a list of local services. On that list, I found one counselling service, but it was a private one. I went to their website and started filling in forms again. Once again I was asked for a lot of personal information, and I had to complete a questionnaire called Core-34. I briefly explained why I was looking for counselling and mentioned that I might be autistic (I’m diagnosed now, but I wasn’t back then). I'm guessing my answers showed that I was feeling much more depressed this time because, honestly, I really was.

Next, I needed to schedule a “registration call” with their admin team. This call was meant to help me understand how counselling works, discuss how long I might have to wait, what the next steps are, and figure out a contribution amount I could afford for my sessions since this is a private service. I was able to get an appointment just a week later. However, I found it frustrating that they only use mobile numbers for communication, and would not accept a landline number. Though fortunately I do own a mobile phone, I’m not a mobile user, and it made me anxious to think that they might send me important information via text that I wouldn’t see until it’s too late. I wonder what prospective patients without a mobile phone would do.

The registration process went really well. Since I only get about £80 a week from Carer’s Allowance, I was not only below their minimum income threshold but also eligible for their support fund. Because of this, we agreed that I would only need to pay £10 for each session I attend once a week, which is a very affordable rate for me. I had been worried I’d be spending the majority of my income on counselling. They told me that I can have up to twenty sessions, but after that, I won’t be able to continue, no matter what. Then we scheduled my assessment appointment, and surprisingly, they had an opening for later that same day, which isn’t usually the case. I was also informed that if I cancelled within 48 hours, I would still be charged, which meant I had to stick with my decision once I accepted, which is fair enough. I did go ahead and accept. Before my appointment, I needed to make a contribution of £10 like any other session, so I was sent a link to a website called “Stripe” to pay it, and I completed the payment.

I had my assessment appointment with a counsellor via a webcam using a service called “Medesk Meet.” It felt a lot like the previous appointment I had with the NHS-TT, but it was more focused on talking about my feelings. The counsellor took notes throughout our conversation. We discussed my treatment goals again, and the term "processing" came up once more. We also talked about some practical things, like when I was available for counselling, and whether I would prefer face-to-face meetings, phone calls, or online sessions. I found out that, even though the waiting list is usually long and can take months, because I had such excellent availability, they thought they could find me a counsellor pretty quickly. Just to clarify, the counsellor I spoke with during the assessment was not the same person I ended up seeing for counselling. In the end, I had my first counselling session nineteen days later.

Having completed the registration process and made the necessary payment, I finally had an appointment lined up— my first counselling session.

Beginning Counselling and Early Experiences

My counselling sessions were for fifty minutes weekly which always felt too short, for a total of twenty sessions. The first session was a bit overwhelming because I was given a lot of new information. We started by reviewing the service agreement, which I’d already read and which had also been explained to me on the phone before, but I suppose it’s part of their induction procedure. I asked if I could take notes during our sessions, and she said yes. She explained that she is a humanistic integrative counsellor, which I didn't quite understand at the time. Then we talked about how I was feeling, what symptoms I was experiencing, and what I hoped to achieve through counselling. This time, I stated my treatment goals as:

-

to be cured of my post-traumatic stress symptoms;

-

to experience at least one day when I don’t think about the incident; and

-

to forgive the person involved.

The word “processing” came up again.

We talked about her counselling methods. One thing that stood out to me was how she kept repeating what I said in a more concise way. While repeating things once or twice in a conversation is pretty normal, she did this all the time. I learned that this technique is called reflective language.

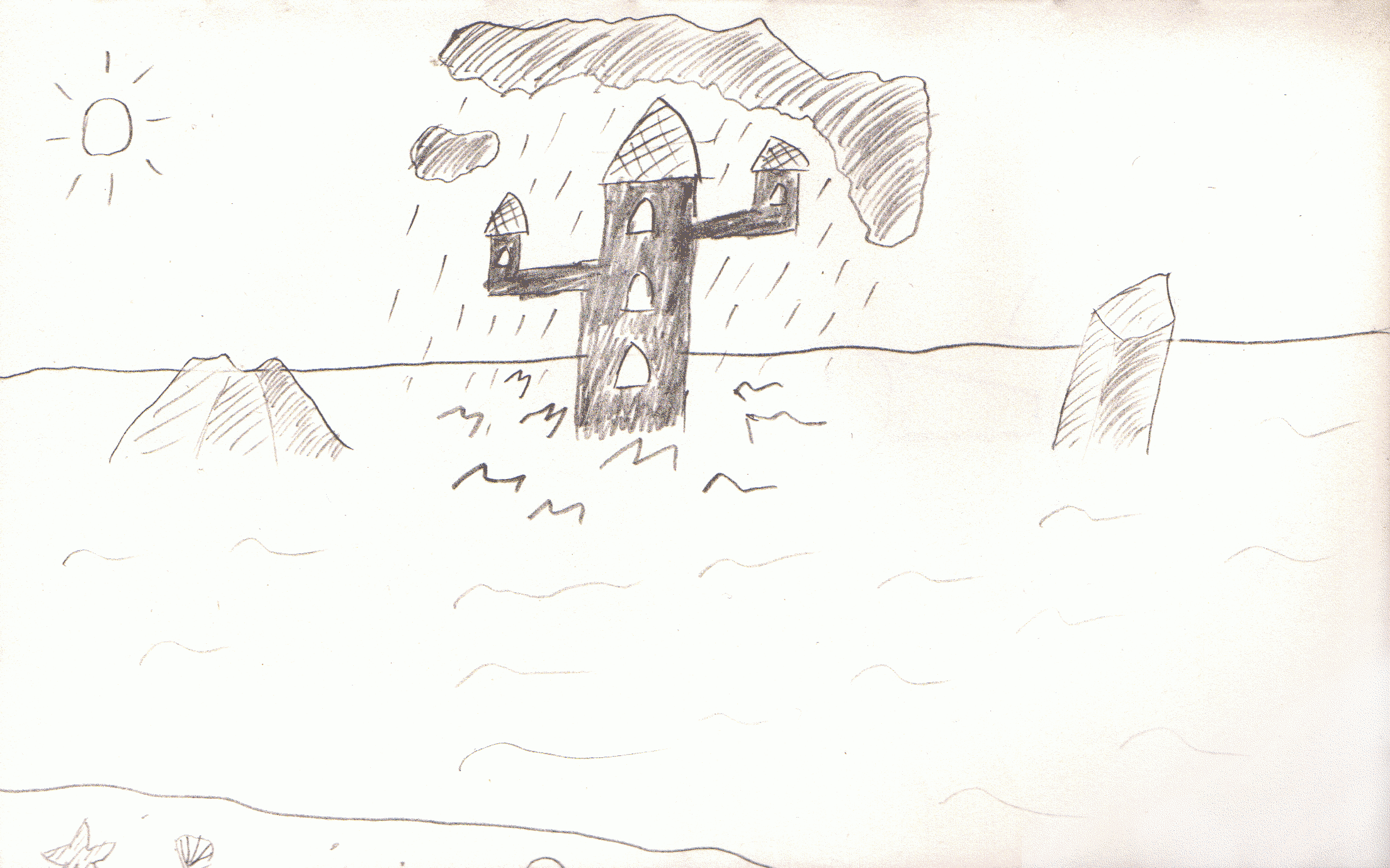

I shared with her a doodle I’d made a few months after the incident—a visual expression of my mental state. She explained that she often encourages clients to draw as part of a method called clean language. When I showed her my drawing, she surprised me by asking, “what is under the ocean?”, by which I presume she meant under the ocean’s surface. When I replied that I hadn’t thought about that, she wondered if it was just a “mirror to the sky”. I suspect this search for symbolism is part of the psychodynamic approach.

I was very upfront that I had doubts about whether this type of counselling would help address my PTSD-like symptoms, but that I was happy to put my faith in the process and see where it leads. We agreed to a six session trial period. My homework was to think about what to talk about next week, as I was in charge.

This took me by surprise, she is the expert, with many qualifications. I didn't expect to be in charge of our sessions. Essentially, I am supposed to use her to fix myself, but I didn’t know how to do that. This was one of the things I wrote down to discuss next time.

I won't go into detail about every session, but I can say that we continued using reflective language and symbol analysis. I think the reflective language has been more helpful because she often explained things in a simple way that makes them seem clearer. The symbol analysis mostly focused on the drawings I've made or the nightmares I've experienced.

She also shared some interesting theories, like suggesting that I might have been using sharing what happened with others as a way to feel more in control; certainly, I’ve felt like I hadn’t had control since my voice had been taken away. When I talked to her about my interests in Georgian, Victorian, and Edwardian society—and especially their art—she said it helped her understand me better. We also talked about how a more structured society like that of the Victorians might suit how my mind works better, or at least it seems more attractive.

During my second session, I talked about the article I was writing about the incident, and my counsellor suggested that we go through it together. She often encourages her clients to write “letters with feelings” to read aloud during sessions.

I didn’t often have specific homework between sessions, so I spent the first few weeks looking into the different methods she uses. I now know that humanistic counselling is an umbrella term for counselling schools that focus on self-discovery, potential, and abilities rather than problems. Essentially the aim is to create a safe, accepting, non-judgemental space where the client can discover what drives them, what their abilities are, and find their own answers. I have noticed that my counsellor is hesitant to say anything that might seem negative about me, even when I tell her it’s okay. This sometimes feels limiting.

The integrative just means my counsellor doesn’t believe there is one therapeutic approach that can help in all situations, and will use whichever approach she thinks would be most appropriate to the client in the moment.

Even as I began to settle into a routine, a lingering question remained: is this generalist approach suited to my needs as an autistic individual?

A Specialist or Generalist?

During my autism assessment, which took place during the same period when I was receiving counselling, the assessors emphasised that I would do best with a counsellor who really understands autism. Later, when my autism assessment report arrived, it included a recommendation for a specialist with experience working with autistic adults, even providing a link to a dedicated service— Cass Counselling.

However, even before all this, when I had been assigned a counsellor, I asked whether she had experience working with autistic clients. I was told that, although their service is generalist, she has worked with some neurodivergent individuals. Naturally, I wondered if she had any specific experience with autism. During my first session with my counsellor, I asked the same question and received the same answer. Nevertheless, I was hopeful that my sessions with my counsellor would be helpful, as I felt we communicated well, not overlooking the fact that she could be a bit too agreeable at times.

I tried to help my counsellor understand what it's like to be autistic, or at least how I experience it. I shared some helpful resources with her, including a guide made by the National Autistic Society and MIND that gives tips for professionals who provide therapy to autistic adults and children. I found out about this guide from my autism assessment report. There are some interesting statistics on the seventh page:

“94% of autistic adults reported experiencing anxiety. Almost 6 in 10 said this affected their ability to get on with life.”

“83% reported experiencing depression. Half said this had a high impact on their ability to get on with life.”

“Almost 3 in 10 fall into the severe depression category based on the PHQ-9.”

“2 in 5 are currently diagnosed with anxiety and ¼ have had a diagnosis in the past.”

“Eight times as many autistic people report feeling often or always lonely when compared to the general population.”

“As anxiety levels increase, life satisfaction decreases.”

“Almost half fall into the ‘severe anxiety’ category of the GAD-7, showing if an autistic person did report experiencing anxiety, it was more likely to be severe.”

“Autistic people reported much lower life satisfaction levels than the general population.”

“The more lonely a person reported they were, the more likely they were to experience greater anxiety and more severe depression.”

As an aside, readers might also find it interesting to know that a study by Rumball et al. (2020) found that approximately 60% of autistic individuals report experiencing probable PTSD at some point in their lives, which is significantly higher than the general population's rate of about 4.5%. Furthermore, a study by A. Shaam Al Abed et al (2024) suggested that autistic people are more likely to form PTSD-like memories from milder stress, and that PTSD-like memories make core autistic traits worse. This study was performed on mice though.

Reflections and Future Hopes

In the end, the counselling wasn’t effective. Throughout my treatment we repeatedly had the same conversation a few times which went something like this:

Me: Every week I feel like I come away with a few more little insights into my condition, but am no closer to treating my symptoms; it’s as though I’m learning around my problems without getting to grips with the central issue.

Counsellor: Experience has taught us that these little nuggets of insight add up over time and lead to real breakthroughs later.

But they never did.

I think talking about my mental health each week was cathartic; it felt good to be able to share what had happened and how it was affecting me week by week. However, it didn't lead to any long-term improvement. Even if I felt better after a session, that good feeling would fade by the evening. Sometimes, I left the sessions feeling more depressed than I did at the start, presumably as I had been thinking deeply about painful memories. In this way, trying to lift my spirits through talking was like a thirst which can never be quenched.

A few months ago I heard a YouTuber say that they’ve been in spaces online where people are hurting, and in the absence of somewhere to work through that pain, they will pour it out into any available container. They emphasised that this is perfectly normal human behaviour. I do wonder if that’s related to why it feels good to talk about my experience even when it doesn’t seem to help me. In fairness to the counselling though, I have learnt things, the issue is that none of my goals were achieved.

Many months passed during which I was receiving no treatment whatsoever, eventually I reached out to NHS Talking Therapies again. That time I made sure to rate my symptoms with higher numbers on the questionnaire. I don’t think this is dishonest, as I had been suffering for over a year with symptoms that make living a normal life impossible. More importantly, people will self report differently. Some people like myself are inclined to be more modest as we don’t want to make a fuss, other people in the exact same position would have reported higher numbers initially. It is disconcerting that treatment will therefore go to the most dramatic patients, not necessarily the worst afflicted.

Anyway, I was accepted by NHS Talking Therapies that time, and am now on a waiting list. I’ve been told it might take up to six months to find someone to treat me. I was initially offered some interim treatment — a course which teaches PTSD sufferers how to better manage their symptoms while they wait for treatment. This offer was subsequently withdrawn on the grounds that it would be best and safer for me to wait for a one-to-one therapy. I don’t understand the reasoning, but there we are.

Conclusion

Although my journey to secure mental health support has been fraught with setbacks—from the impersonal rejections of NHS Talking Therapies to the challenges of navigating private counselling—I remain determined to find a path forward. Each step, no matter how small, has forced me to confront my ongoing struggles with depression, anxiety, and intrusive memories. Sharing these experiences is not just a personal catharsis, but a call for a more understanding and inclusive support system for those of us who are neurodivergent, and frankly those of us in general.

I hope that by shedding light on the complexities and frustrations of this process, others in similar situations feel less alone. It would be nice to think it might also lead professionals to consider more tailored approaches to mental health care, but I doubt any will read this. While progress is slow and the road ahead remains uncertain, I have to believe that reclaiming my voice—and my life—is worth the effort.